What Should You Be Doing: Fundraising or Pursuing Grant Money?

May 03, 2020

If your organization needs funding (and what organization doesn’t?), you have three primary options for raising funds: (1) you can solicit donations from individuals, (2) you can submit proposals to foundations and government agencies to receive grant funding, or (3) you can hold fundraising campaigns and community events to collect donations.

While the motivation behind all three is similar—to collect sources of revenue to support programs and core operations—the resources you need and the tasks involved are different for each one. They are not interchangeable paths to generating revenue. For some organizations, grant funding is an appropriate pursuit, although no organization should rely 100% on grant funding (for more on this, see the post Should You Be Relying on Grant Funding? ). For other organizations, grants are not going to be a good fit either because the organization lacks the capacity to write grants or because the organization’s greatest need is for core support (unrestricted funding).

Based on hundreds of emails we’ve received since we launched Peak Proposals in 2015, we have observed that many people appear to assume that if you are a nonprofit organization and if you need revenue, then you must pursue grant funding.

This is not the case. While grants are one way an organization can generate revenue, for many organizations, grants should not be pursued as aggressively as other forms of revenue generation. In fact, for many nonprofits, grant funding may not be worth pursuing at all.

To help you determine whether your organization should focus on grant funding, we’re going to review the relationship and differences between fundraising and grant funding. By the time you finish this post, we hope you’ll have a clearer idea of what is involved with each of these activities and which activity is more likely to generate revenue for your organization.

WHAT DOES FUNDRAISING INVOLVE?

Grant funding is a way to raise funds, so in that regard, it technically falls under the broader category of fundraising. However, fundraising typically refers to generating cash donations by either cultivating individual donors; by holding fundraising events such as auctions or athletic events such a 5K race; or through an ongoing, general appeal for donations through a website or mail-based campaign.

Central to the idea of fundraising is the collection of cash donations. The donations can be collected immediately or over a period of months or years, as is the case for long-term pledges.

Fundraising requires skills in areas such as event planning and donor cultivation. To be successful at fundraising, you have to be willing to ask people to donate money to your cause. This is not something everyone is comfortable doing and is quite different from pursuing grant funding. When you submit a grant application to a foundation, it is a pitch of sorts, just like you might make a pitch to an individual donor, but the relationship between you and the funder is more formalized and less personal. When pursuing grant funding, you’re submitting a proposal to an entity that exists for the very purpose of giving money to organizations. Additionally, the funder’s past giving history is often made accessible to the public. In contrast, with individual donors, you may be soliciting funds from individuals whose financial circumstances, family situation, and philanthropic interests are largely unknown to you.

Mistakes Organizations Make in Fundraising

In terms of areas where organizations struggle with fundraising, the main challenge we’ve seen is that organizations overestimate the amount of money they think they can generate from a fundraising activity and underestimate the cost of doing the fundraising.

Some fundraising events can require a nonprofit to commit hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of dollars upfront, which is money the nonprofit risks losing if the event is unsuccessful. For a fundraising event to be worthwhile, the nonprofit needs to do more than just recoup its costs. It must generate a decent profit to justify the commitment of human and financial resources.

While this type of analysis may seem obvious—of course the nonprofit wants to generate a profit!—nonprofits can fall into the habit of holding annual fundraisers without critically assessing whether the event is a good return on investment. In particular, if the nonprofit must hire staff to manage its fundraising activities, a cost/benefit analysis is an essential exercise. If a nonprofit has to pay someone $50K/year (out of unrestricted funds, the most difficult type of funding to generate) to manage fundraising activities that generate $35K/year for the organization, it doesn’t make sense. Regardless of the size of your organization or budget, you must look critically at the potential return on investment of any fundraising activity.

How Do Nonprofit Organizations Staff Fundraising and Proposal Writing Activities?

In larger nonprofit organizations, you usually see two separate units or departments, one group focused on managing fundraising efforts, and a second group focused entirely on grant funding. In smaller nonprofit organizations, it’s common to have the same people (and in a very small organization, possibly just one person) engaged in both fundraising and proposal writing. At institutions of higher education, the fundraising division, which may handle corporate as well as individual donors, is often organized under the label of “advancement."

In terms of the level of effort, both fundraisers and grant writers typically have a cyclical workflow. Foundations generally release opportunities at set times throughout the year, and an organization’s fundraising activities often center around a calendar of events, many of which will be annual. In large nonprofits, volunteers play little or no role in preparing grant proposals and are often not engaged with fundraising activities. The one exception to this is the nonprofit’s board members, who may be required to donate to the organization and expected to solicit donations from their professional and social networks. In smaller organizations, volunteers are often an essential component of any fundraising event, although less likely to be used for grant writing.

WHAT IS REQUIRED TO SECURE GRANT MONEY?

Our blog includes several posts that discuss in depth what is involved in pursuing grant funding. In brief, to secure grant funding, there are three key steps:

You need to be clear what you need the money for (e.g., a specific program or general operating expenses).

You need to research prospective funders—which could be private or corporate foundations or public agencies—to identify those funders and funding opportunities that are the best fit for your organization.

You have to have the capacity and skills to pull together a well written, competitive grant application that has (by your estimation) at least a 50/50 chance of being funded (i.e., the funders you’ve chosen to apply to are reasonable targets given your experience and past accomplishments).

Mistakes Organizations Make In Pursuing Grant Funding

There are two mistakes we see organizations frequently make in their pursuit of grant funding:

They fail to thoroughly research potential funders: Organizations frequently focus a great deal of effort on finding open funding opportunity announcements (FOAs). However, they often fail to perform adequate research on the funders releasing the FOAs.

Before you commit to preparing a grant application, you should be confident that your organization is a good match with the funder’s interests and mission and that your organization would be a competitive applicant.

If you see that a foundation has a funding opportunity that is a good fit for one of your program areas, that’s the first hurdle. Next, you need to investigate a little further to see if your organization is the type of organization the funder typically funds. If you are planning to apply to a foundation for support, you should look at the foundation’s list of past grantees, which are usually listed on the foundation’s website. Does your organization compare favorably to the organizations that have received grants in the past in terms of programmatic and geographic focus, organizational capacity, and operating budget? If the answer is “no,” it might be time to move on and look for other funding opportunities.

They spend too little time preparing their grant applications: Another common mistake we see among organizations of all sizes and levels of sophistication is a failure to dedicate enough time to the proposal development process. Not all grant applications require weeks and months of labor. Many applications from smaller foundations are a simple fill-in-the-blank form. However, even with short grant applications, maybe even particularly with short grant applications, it’s imperative to compose thoughtful answers. Every word counts when you have limited space to persuade the funder you’ll be an ideal grantee.

While it’s appropriate to scale your efforts to the potential award value of the grant—for example, it makes sense to put more effort into a grant worth $100K than $3K—for grants of any size, your grant proposal should come across as professional and persuasive. At a minimum, your application should be clearly written, have no glaring grammatical issues, and be correctly formatted. For most grant applications, even short ones, you’ll need at least a couple of weeks to draft the application and complete at least one cycle of revisions prior to submitting it.

Do you need money now...or in 6–12 months? Do you need money for projects...or for general operating expenses? The answers to these types of questions will help you determine if you should put more effort into fundraising versus grant writing.

SIMILARITIES BETWEEN FUNDRAISING ACTIVITIES AND GRANT FUNDING

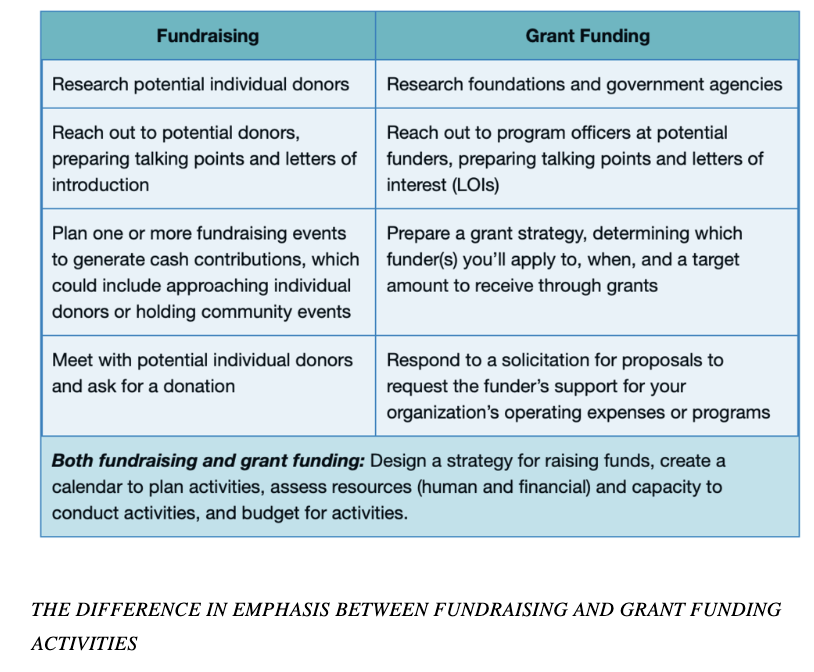

With both fundraising activities and the pursuit of grant funding, you need to do research, pursue leads, prepare talking points, evaluate opportunities, and cultivate relationships. The spirit of the activities is the same, it’s the focus and context that are different.

SHOULD YOU BE FUNDRAISING OR PURSUING GRANT MONEY?

When Fundraising Makes Sense: You Are Facing a Short Time Frame and Need Total Flexibility in Spending

Fundraising makes sense when you need revenue for general operating expenses such as rent, utilities, and to cover administrative staff salaries. Fundraising also makes sense if you need revenue immediately or within a short time frame, such as the next 3 months.

Fundraising campaigns require planning and time for execution, so it’s not an instantaneous solution for funding woes. However, you have more control over the timeline for a fundraising campaign than you do over a grant funding cycle.

Foundations and government agencies can take months to review grant applications and make a funding decision, and at the end of that potentially lengthy wait, you may learn you have not been funded. With fundraising activities, you are able to launch a campaign and track its progress on a day-to-day basis, making adjustments to your strategies as you go along. With fundraising, you set the funding target, you establish how you’ll conduct the campaign, and you always know where you stand relative to your goal. Additionally, any money you raise through a fundraising campaign can be spent as you see fit, which could be for general operating expenses or program costs.

In most cases, fundraising is a better match for organizations that rely heavily or exclusively on volunteers. Community members are often willing to rally around a cause and donate money based more on the work being done than who is doing the work (volunteers, paid staff, or a combination of the two). In comparison, a foundation or government agency may hesitate to fund (read: invest in) a project if the applicant organization cannot provide a list of personnel with the right expertise and skills who are committed to carrying out the project if it is funded. Although volunteer staff can be very committed to an organization, if you have paid staff, it will help to assure the funder that you’ll be able to achieve the project goals.

When Grant Money Is Worth Pursuing: You Don’t Need Funding Urgently and You Seek Funding for a Specific Project

As mentioned earlier, pursuing grant funding should not be your default strategy if you need funding. That said, there are times when seeking revenue from grants is not only entirely appropriate but also the best strategy.

Because it can take a considerable amount of time to identify relevant grant opportunities, trying to fund your organization through grant money works best when it is part of a long-term funding strategy. If you can wait for 6–12 months to receive funding, a grant becomes an option worth considering.

If you need funding more urgently, grant funding is not ideal. With grant funding, there are too many variables outside of your control that make it difficult to predict when (or if) you’ll receive funding. These variables include the timing of when the funder releases the funding opportunity announcement; the level of competition for funding; and how long it takes for the funder to review applications, come to a funding decision, and send the money to grantees.

With fundraising, you have control over two key variables: when the fundraising campaign or event launches and when it will end. You also can access any money you raise pretty much immediately, whereas, with a grant, funders often spread the award payments over several quarters or years.

When to Pursue both Fundraising and Grant Funding Activities

If your organization has the capacity to fundraise and write grant proposals, that’s the best strategy of all because it diversifies your income stream. Fundraising and proposal writing require different skill sets, so part of what you’ll need to determine is whether you have the right configuration of staff and volunteers to take on both types of activities.

If your organization relies heavily on volunteers, fundraising activities can be an excellent way to use a volunteer workforce. Volunteers can also be used as grant writers, but it can be harder to find a volunteer who has the grant writing skills you need than to find someone who has the energy to help with a fundraising initiative.

If you determine that you should (and can) pursue a joint strategy of fundraising and grant writing, a key first step is to identify the resources you have for each activity, human as well as financial, and what your priorities are. Going back to the question of timing, you may be able to pace yourself by focusing on one revenue-generation activity, such as a fundraising campaign, while you build your infrastructure to pursue grant funding.

SUGGESTED NEXT STEPS

We hope this post has given you some ideas regarding the best funding strategy for your organization. To read more about topics covered in this post, please see:

Another way nonprofits raise funds is to launch a revenue-generating enterprise, which is a different model that traditional fundraising activities. If you’re interested in learning more about this approach, we suggest you read our post Paths to Nonprofit Sustainability.