The Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community is incredibly diverse, consisting of numerous ethnicities, cultures, origin countries, languages and socioeconomic backgrounds. While AAPI is a term that unifies many, the AAPI community is far from monolithic. Local leaders must acknowledge and embrace the diversity within it. By recognizing the diverse experiences of AAPI renters and homeowners, tailored programs can be developed to support them.

Note: While AAPI is a term that unifies many, it is an inexact term. The terms used in this blog (Asian, AAPI) are used interchangeably not to cause intentional confusion, but because there is no universal agreed upon definition or categorization. Some studies cited refer to the “Asian” population broadly, but do not specify which countries of origin are included. This is a broader reflection for the need for shared definitions and data disaggregation, however, not the main topic of this blog.

Who are AAPI Renters and Homeowners?

As of 2021, the AAPI community, comprised of the U.S. Census Bureau’s “Asian” and “Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander” racial categories, makes up 5.9 percent of the overall population. Within this group, there are six primary heritages: Chinese (23%), Indian (22%), Filipino (15%), Vietnamese (10%), Korean (8%) and Japanese (4%). However, there are numerous other countries of origin that fall into the “Other” Asian and “Other” Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander categories, including Pakistani, Cambodian, Hmong, Thai, Bengali, Mien, and more.

Dispelling Common Misconceptions

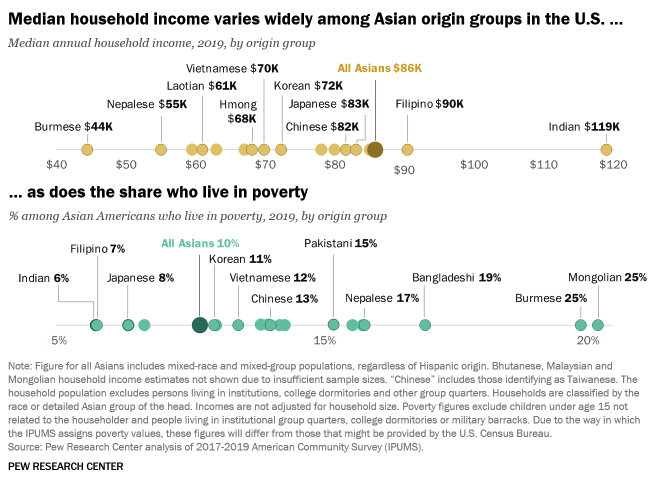

One of the prevailing misconceptions is that Asians (broadly defined) excel in terms of economic well-being compared to the broader U.S. population and other racial/ethnic groups. On the surface, census data seems to support this claim, indicating that Asian Americans outperform other groups in terms of income, homeownership, rates and more. However, these aggregate statistics hide significant disparities in key measures of well-being. For example, while Asian American households have the highest median income compared to all other race/ethnicity, there is a substantial disparity in earnings across different Asian origin groups, more so than in other racial/ethnic communities.

Similar disparities emerge when we compare “Asian” with “white” or “Black” or other racial/ethnic groups when looking at data on higher education attainment. In 2022, 59.3 percent of the Asian population held a bachelor’s degree, compared to 41.8 percent of the non-Hispanic white population; 27.6 percent of the Black population, and 20.9 percent of the Hispanic population. However, the share of those with a bachelor’s degree range from 72 percent among Indians, to just 9 percent among Bhutanese.

Blanket statistics that just focus on the AAPI community in aggregate create a false portrait of the AAPI as uniformly well off. This misconception ultimately undermines many of the struggles that AAPI individuals face with housing stability, poverty and educational attainment. Moreover, the model minority myth can often morph into an implicit criticism of other racial/ethnic groups.

What barriers do they face?

According to one study of seven cities, one in four AAPI households are severely housing cost-burden, paying more than half of their income towards housing costs, though this varies widely across ethnic subgroups and geography. A significant share of the severely cost-burdened households is limited English proficiency household. Without culturally competent and language-specific resources, many of these households may fail to connect to the resources that can support them. One study found that 54 percent of severely cost-burdened Asian households are Limited English Proficient compared to 9 percent of severely cost-burdened white households.

What can cities do?

Disaggregate any data on AAPI residents across subgroups

Because there is such disparity in income and educational attainment, it is imperative to disaggregate any data on AAPI residents across subgroups. Failing to disaggregate data erases the experience of those at the lowest end of the spectrum. Furthermore, the issues that are important to AAPI residents will vary widely across subgroups, often by origin or by income.

States such as California and New York have signed bills that require data on the AAPI community be disaggregated. These are the first important steps for more government actors—local, state and federal, to begin understanding how diverse the AAPI community is.

For example, Austin, TX City Council adopted a resolution calling for a quality-of-life check on the city’s Asian community, across many different facets of local government including access to services, housing, jobs, mobility, health care, and translation/interpretation services. The resultant report provides key recommendations including to improve language access programs, draft multicultural outreach and engagement plans, improve affordability, education on discriminatory practice in housing and more. This survey considered all varying identities and origin countries, including 28 Asian ethnicities representing 25 different countries.

Prioritize language accessibility, particularly for severely cost-burdened households

Without language accessibility, households that may need programs and support may not actually know they exist. Prioritizing language accessibility means analyzing dominant non-English languages spoke in limited English proficiency households and partnering with cultural institutions to help spread the word about available support. Working with trusted partners can help mediate across language barriers and potential cultural stigma around receiving government support. The District of Columbia has had a Mayor’s Office on Asian and Pacific Islander Affairs since 1987, to promote and engage the District’s AAPI residents and business owners and mediate between the mayor’s office and AAPI community.

Recognize the affordability challenges that many lower-income AAPIs face

There is a real problem with affordability for low-income AAPIs – both renters and homeowners. For example, low-to-moderate income AAPIs are far less likely to own a home compared to white households in the same income group. Similar nuances appear when disaggregating data across other income groups, or other racial/ethnic origins. More cities should target efforts to ensure stable housing and homeownership to the AAPI community. Disaggregated data will help identify the most vulnerable.

Consider the different types of housing arrangements (whether rent or owned) that AAPI households want

AAPIs are more likely than white households to live in multigenerational housing, meaning two or more adult generations living together in the same home (e.g., a household with a 7-year-old, their parents, and a grandparent or two adult siblings living with their parents would both be considered multigenerational housing). The reasons for choosing multigenerational housing are complex and varied, but may be a cultural choice, out of economic necessity, for caretaking purposes, or some combination of all those reasons and more. Furthermore, the limited data that is available on condos, an important form of multifamily home ownership and a key pathway to first-time homeownership, suggests that Asian households tend to have higher rates of condo ownership over other racial/ethnic group. While more research is needed to figure out why, it is significant that the rates of condo ownership at highest among the Asian population. Multifamily for-sale construction is near historic lows, potentially leaving the AAPI community without choice. Recognize the diversity of housing arrangements that suit the AAPI community and prioritize meeting those needs.

AAPIs are one of the fastest growing racial groups in the United States. To effectively support AAPI renters and homeowners, local leaders must first recognize how diverse the AAPI community really is. Doing so is the first step towards shaping policies and programs that alleviate the housing challenges they face and accommodate their housing aspirations.