Football to Manufacturing: The Divergent Path of Nearby Competitors

Article by Joseph Zhong

Imagine you are a five-star quarterback that grew up in Alabama, with guarantees that you would be the starting quarterback your freshman year. Which school would you pick: the University of Alabama or Samford University? The answer is obvious: University of Alabama. But why did you choose it? The coaching staff, training facilities, and other players give you the complementary infrastructure to succeed.

When corporate boards decide to move manufacturing operations overseas, they similarly focus on complementary infrastructure when choosing a destination. Some countries have an inherent advantage when it comes to manufacturing because previous companies have built existing infrastructure that improves the productivity of investment; this results in the coalescing of industries within one particular country while other previously similar countries remain puzzlingly abandoned; this path-dependence is also known as manufacturing bifurcation.

For an example of manufacturing bifurcation, we present the natural experiment of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The two countries have similar geographies, sharing one island; similar population demographics; similar religious diversity; and both suffered from a colonial past. With few differences between the two island countries, they present a useful natural experiment to look into the validity of bifurcation to see if a single event could precipitate lasting differences from initial similarity.

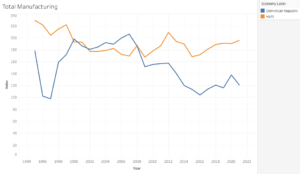

We used the comparative advantage index from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development to look at the manufacturing sectors between the two countries. When aggregating all manufacturing activities together, we see no evidence of manufacturing bifurcation (Figure 1). However, manufacturing has different categories from labor-intensive to technology-intensive with attendant different levels of technology. Breaking down manufacturing into these two categories, we begin to see some stark differences emerging between the two countries.

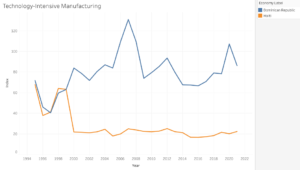

First, looking at technology-intensive manufacturing, we see that the Dominican Republic began to outpace Haiti around 1999, resulting in a coalescence of technology-intensive manufacturing in the Dominican Republic while Haiti completely lost their manufacturing sector. The two countries have diverged in manufacturing with little signs of a return to parity.

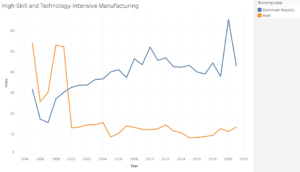

Looking specifically at the high-skill technology-intensive manufacturing, we see a starker difference. The Dominican Republic slowly built up its high-skill technology-intensive manufacturing while Haiti lost their high-skill technology-intensive manufacturing. Haiti has yet to regain any semblance of the dominance it had on the high-skill technology-intensive manufacturing advantage it had over the Dominican Republic.

One potential explanation of the manufacturing bifurcation is that technology-intensive industries inherently require stable government, strong property rights, high-quality institutions, educated workforce, and resilient physical infrastructure. Technology-intensive industries require companies to invest high amounts of capital to create the conditions conducive to the successful manufacturing of their product. The Dominican Republic had democratized and become a fairly stable country after the assassination of Trujillo, a Dominican dictator, in 1961. Haiti was perceived as a secure nation by the international community because it was under United Nations occupation from 1993 through 1999. With increased guarantees from the United Nations for political stability and physical security, companies invested in Haiti at the same rate as the Dominican Republic. Therefore, both countries had similar levels of technology-intensive manufacturing, with a slight edge to Haiti given US and UN guarantees.

When the United Nations set an end date for its occupation, companies began scrambling out of Haiti because of perceived lack of political stability in Haiti. Many companies crossed the border to the Dominican Republic, leading to the two countries switching comparative advantages in high-technology manufacturing. The results became widely apparent after 2003 when GDP and Gross Value Added (GVA) in the Dominican Republic grew exponentially in comparison to Haiti; technological investments in a country take a few years to pan out.

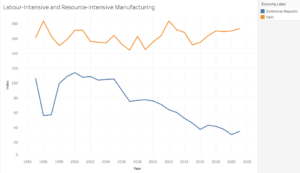

Source: World Bank

Moreover, the explanation seems even more fitting when looking at the decline of labor-intensive manufacturing in the Dominican Republic. As the Dominican Republic embraced more technology-intensive manufacturing and experienced greater economic growth, the cost of living and wages increased. Therefore, the Dominican Republic became less appealing for labor-intensive manufacturing, despite the generous tax benefits offered by the Dominican government to incentivize companies to move to the Dominican Republic. On the other hand, because of a failure to raise standards of living and wages, Haiti has consistently been able to provide cheap labor. These industries would seem to be less reliant on a stable political climate.

Through our graphs, we can see that manufacturing bifurcation did indeed happen between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, with the Dominican Republic developing a comparative advantage in high-skill and technology-intensive manufacturing and Haiti taking advantage of more labor-intensive manufacturing industries. Given this newfound understanding of manufacturing bifurcation, we are faced with new questions. Is Haiti forever doomed by the Dominican Republic’s domination of high-skill and technology-intensive manufacturing, given no signs of recovery from Haiti? Certainly not as from the graphs and a historical recounting, we saw that Haiti and the Dominican Republic switched their comparative advantage in the late 1990s; given this evidence, how can Haiti redevelop its high-skill and technology-intensive industries and should it redevelop?

Regardless of what the future holds for the two countries, one thing is for sure: the Dominican Republic will continue to have a significant comparative advantage in and higher concentrations of high-skill and technology-intensive industries and Alabama will continue to have a higher concentration of NFL draftees unless Haiti and Stamford somehow change their infrastructure to be attractive to free agents.